Popular

Tips for Controlling Blood

Pressure: What Diet & Exercise Can Do

Evelyn

Smith

MS

in Library Science, University of North Texas, 2012

Since

vascular dementia makes up ten percent of all dementia cases,

middle-aged and older adults should review these tips for helping to

control hypertension (Types of dementia, 2015, para. 5). Admittedly,

some of the tips for lowering the risk of Alzheimer's disease--such

as watching blood sugar by reading product labels, limiting carbohydrates and choosing

healthy fats, like olive oil and wild fish, cramming a minimum of 20

minutes of sustained aerobic exercise into a daily routine, and

lowering cholesterol levels—might also lower blood pressure (Rushlow, 2014, October 21, para. 78, & 10).

Although

concentrating on blood pressure might seem to take older adults back

to the days when dementia was synonymous with “hardening of the

arteries”, many of the tips for delaying or preventing Alzheimer's,

such as engaging in continuous aerobic exercise and keeping a

heart-healthy Mediterranean-style diet also substantially lower blood

pressure naturally. Anstey, Cherbuin, and Pushpani, for example,

identify eleven risk factors for Alzheimer's that include a high body mass

index (BMI) and a high serum cholesterol level, diabetes, smoking, and heavy

alcohol intake as well as four protective factors, such as

participating in high levels of physical activity and regularly

eating fish, that affect both cardiovascular health and the chance of

developing Alzheimer's or other types of dementia (Anstey, 2013,

August, Abstract).

References:

Anstey,

K. J., Cherbuin, N., Pushpani, M. H. (2013, August). Development

of a new method for assessing global risk of Alzheimer’s Disease

for use in population health approaches to prevention.

Accordingly,

anyone interested in delaying or preventing dementia should also look

into tips for lowering blood pressure, followed by longitudinal

studies that back up the recommendations as well as some occasional

helps to help readers achieve their heart and cardiovascular

system-healthy goals:

Maintain

a healthy weight;*

Be

physically active

[Exercise aerobically for at least 30 minutes at least five days per

week];*

Follow

a healthy

[DASH] eating

plan;*

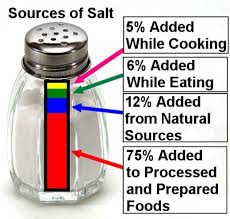

Reduce

sodium in your diet;

Drink

alcohol only in moderation;

Take

prescribed drugs as directed.

(NHLBI,

2003, p. 17)

*Aerobic

Exercise & a Low Fat Diet Reduces Hypertension

|

| Couple diet and exercise to reduce both your blood pressure and your waist line. |

So who needs to watch out for high blood pressure?

Hypertension risk

groups. (2014, March 30). Resperate. Retrieved

from http://www.resperate.com/hypertension/hypertension-risk-groups?utm_source=RESPeRATE+USA&utm_campaign=a4306ea230-LP_News_recipe_US_2015_4_16&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_ac3cc1206e-a4306ea230-297127657&ct=t(LP_News_recipe_US_2015_4_16)

The overweight

(or those with a BMI over 25) as well as women and those in lower

income groups are most likely to have high blood pressure. Moreover,

according to a World Health Organization study, high blood pressure

is responsible for 12.5 percent of all deaths worldwide

(Hypertension, 2014, March 30, para. 1-2).

Risk

factors for high blood pressure:

- Obesity;

- Low income;

- Female

gender: High-income older women are more likely to try to actively

control their blood pressure;

- Heavy

drinking

(Hypertension,

2014, March 30, para. 3-4)

People from

all walks of life in hypertension risk groups

Even more those

who know they suffer from hypertension, the death rate for high blood

pressure is “strikingly high” in low and middle-income countries.

The WHO study also underlines the necessity of monitoring blood

pressure after age 40 since hypertension is a silent killer

(Hypertension, 2014, March 30, para. 5).

Hypertension

risk groups for secondary hypertension

Underlying

conditions—like Cushing's, Lupus, type 2 diabetes, and kidney

disease as well as taking oral contraceptives—can cause secondary

high blood pressure. Cocaine and amphetamines also raise blood

pressure (Hypertension, 2014, March 30, para. 6).

Accordingly, along with regularly monitoring for hypertension, adhering to a Mediterranean style diet along with fitting at least 30 minutes of aerobic exercise into a daily schedule, and loosing weight, so the Body Mass Index falls below 25, goes a long way toward controlling high blood pressure:

------------

Asikainen, T. M., Kukkonen-Harjula, K., and Miilunpalo, S. (2004). Exercise for health for early postmenopausal women: A systematic review of randomised controlled trials, 34(11), 753-78. Sports Medicine (Auckland, New Zealand). [Abstract only]. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15456348

A systematic review of randomized, controlled exercise trials of post menopausal women aged 50 to 65 years reveals that early postmenopausal women can benefit from 30 minutes of moderate walking daily combined with a resistance training program twice a week, thus improving their flexibility, balance and coordination and decreases hypertension as well as lowering the abnormal amount of cholesterol and fat in the blood.

Bacon,

S. L., Sherwood, A., and Hinderliter, A. (2004). Effects of exercise,

diet and weight loss on high blood pressure. Sports

Medicine

(Auckland, New Zealand), 34(5), 307-16. [Abstract only]. Retrieved

from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15107009

Exercise

alone reduces systolic and diastolic blood pressure approximately

3.5 and 2.0 mm Hg respectively.

Following

a DASH diet that emphasizes low-fat dairy products and fruits and

vegetables, reduces SBP and DBP 5.0 and 3.0 mm Hg respectively when

compared with following a standard American diet.

Both

exercise and weight loss decrease left ventricular mass and wall

thickness, reducing arterial stiffness and improving the functioning

of the inner lining of the blood vessels.

The

original DASH diet require the dieter to reduce his or her sodium

intake or lose weight to be effective, but recent findings show that

combining the original DASH diet with sodium reduction more

effectively lowers blood pressure than following the original DASH

diet plan alone. The DASH diet emphasizes fruits, vegetables, and

low-fat dairy products.

Glassberg,

H. and Balady, G. L. (1999,September-October). Exercise and heart

disease in women: Why, how, and how much? Cardiology

in Review,

(5) 301-8. [Abstract only]. Retrieved from

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11208241

One

quarter of all American adults are sedentary, and 1/3 of all women

don't take part in any leisure time physical activity. Studies,

however, note that women who exercise reduce their blood pressure and

improve their lipid profiles while lowering their likelihood of

developing diabetes. The Centers for Disease Control, the American

Heart Association, and the American College of Sports Medicine thus

recommend that everyone should participate in weight-bearing, aerobic

exercise at least three to five days per week. Aerobic exercise can

also help to prevent osteoporosis in women.

Hagberg,

J. M., Park, J. , and Brown, M. D. (2000, September). The role of

exercise training in the treatment of hypertension. Sports

Medicine

(Auckland, New Zealand), 30(3), 193-206. [Abstract only]. Retrieved

from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10999423

Exercise

decreases blood pressure in approximately 75 percent of all

individuals diagnosed with hypertension. Women are more likely to

reduce blood pressure through exercise than men, and the middle aged

accrue more benefits from exercise than young adults and the elderly.

Low to moderate exercise also more efficiently reduced blood

pressure than high intensity exercise, and the more one exercises,

the greater his or her healthy benefits will be. However, a single

exercise session can reduce blood pressure for a 24-hour period.

Ishikawa-Takota, K.Ohta,T,

and Tanaka, H. (2003, August). How much exercise is required to

reduce blood pressure is essential to reduce blood pressure in

essential hypertensives? A dose-response study. American

Journal of Hypertension,

16 (8), 629-33. [Abstract only]. Retrieved from

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12878367

Previously

sedentary individuals diagnosed with hypertension can significantly

decrease their blood pressure by modestly increasing their physical

activity, according to the results of an eight-week exercise program

of 207 untreated subjects diagnosed with stage one or two

hypertension. Researchers divided participants into a control group

whose members exercised only 30 to 60 minutes per week, volunteers

who exercised from 61 to 90 minutes a week, 3) participants who

exercised from 91 to 120 minutes per week, and 4) individuals who

exercised over 120 minutes per week. Systolic and diastolic blood

pressure at rest didn't change for the control group, but individuals

in all other groups experienced a significant reduction in systolic

and diastolic blood pressure.

Lakka,

T. A. and Bouchard, C. (2005). Physical activity, obesity and

cardiovascular diseases. Handbook

of

Experimental Pharmacology,

(170), 137-63. [Abstract only]. Retrieved from

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16596798

Regular

physical activity for 45 to 60 minutes daily prevents unhealthy

weight gain and obesity whereas sedentary behaviors . . . promote

them.” The “optimal approach”, however, in weight production

programs combines regular physical exercise and a restriction of

calories. A minimum of 60 minutes of moderately intense physical

exercise, however, may be needed to avoid or limit weight gain in the

formerly obese.

Lin,

P. H., Ackin, M., and Champagne, C., et

al.

(2003, April). Food group sources of nutrients in the dietary

patterns of the DASH-sodium trial. Journal

of the American Dietetic Association,

103(4),488-96. [Abstract only]. Retrieved from

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12669013

The

DASH dietary pattern recommends that dieters drastically cut their

intake of meat, but they should increase their servings of fruits and

vegetables. That means consuming four to five servings of fruits,

four to five servings of vegetables, two to three servings of low-fat

dairy products daily while limiting servings of beef, poultry or fish

to twice a day, making up for this with four to five servings of

legumes, nuts, and seeds weekly.

Lin,

P. H., Appel, L. J., and Funk, K. (2007, September ). The PREMIER

intervention helps participants follow the Dietary

Approaches to Stop Hypertension

dietary pattern and the current Dietary Reference Intakes

recommendations. Journal

of the American Dietetic Association

107 (9), 1541-57. [Abstract only]. Retrieved from

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17761231

This

18-month, randomized, controlled trial followed 810 participants aged

25 and older with a BMI between 18.5 and 45.0, who were not taking

anti-hypertension medications and had been diagnosed with

pre-hypertension or stage one hypertension (SBP 120 to 159 mmHG and

DBP 80 to 95 mm Hg). Both the intervention group controls and those

participants who followed the intervention protocols as well as the

DASH diet plan substantially reduced their total fat, saturated fat,

and sodium intake and ramped up their intake of fruits, vegetables,

and dairy products. However, only those individuals who followed the

established intervention plan plus the DASH diet plan significantly

increased their intake of DASH specific food groups, rich in

potassium fiber, calcium, and magnesium. Researchers thus concluded

that a greater emphasis on “nutrient dense” food with improve

future dietary interventions.

Mendes,

R., Sousa, N., and Garrido,N., et

al.

(2014, November 12). Can a single session of a community-based group

exercise program combining step aerobics and body weight resistance

exercise acutely reduce blood pressure? Journal

of Human Kinetics,

43,49-56. doi: 10.2478/hukin-2014-0089. [Abstract only]. Retrieved

from

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25713644

A

single, 50-minute session of exercise combining step aerobics and

body resistance training significantly reduced post exercise blood

pressure in a group of 23 healthy young women in their 30s. The

program consisted of a five minute warm up of aerobic dance

exercise, 30 minutes of step aerobics, 10 minutes of resistance

exercise training, and a five-minute cool down of breathing and

flexibility exercises.

When

an obese individual's BMI is greater than or equal to 30 km/m2,

mortality rates from all causes, especially cardiovascular disease,

increases by 50 to 100 percent. Thus, strong evidence exists that

weight loss in the over weight improves risk factors for diabetes and

cardiovascular disease. Weight loss reduces blood pressure in

overweight hypertensive and nonhypertensive [or prehypertensive]

patients, reduces serum TG levels, increases high-density lipoprotein

cholesterol levels, and may reduce low-density lipoprotein

cholesterol concentrates . . . Therefore, “30 to 45 minutes of

physical activity of moderate intensity should be encouraged. All

adults should set a long-term goal to accumulate at least 30 minutes

of moderate-intensity exercise on most, and preferably all days . .

.” Finally, those trying to lose weight after consulting a

physician should set a realistic weight loss goal of approximately

0.5 to one pound per week.

Schwartz,

J.B. (2015,April). Primary prevention: Do the elderly require a

different approach? Trends

in

Cardiovascular Medicine,

25(3), 228-239. [Abstract only]. Retrieved from

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25560975

While

trial data remains sparse for adults aged 75 to 80, primary

prevention strategy decisions at this stage of life should consider

estimated life expectancy and over all function as well as examine

cardiovascular event risks and access a benefit to harm ratio. Even

so, limited data supports the use of moderate aerobic exercise to

lower systolic hypertension, thus reducing the risk of cardiovascular

disease and dementia while also taking into consideration the

possibility that participants might fall and injury themselves while

exercising. While trial data on exercise alone is not available, a

review of “multi-system benefits” proves that exercise should

continue to be part of a preventive regime in the eldest elderly.

Solfriezzi,

V., Panza, F., and Frisandi, V. (2011, May). Diet and Alzheimer's

disease risk factors of prevention: The current evidence. Expert

Review of Neurotherapeutics,

11(5):677-708.

doi: 10.1586/ern.11.56. [Abstract only]. Retrieved from

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21539488

Elevated

saturated fats may help increase the effects of age-related cognitive

decline while current evidence links regular fish consumption

[usually amounting to at least two servings of fish rich in omega 3

fatty acids weekly] reduces the risk of dementia as does light to

moderate alcohol consumption [That amounts to a glass of red wine

with the evening meal]. Poorer cognitive function and an increased

risk of vascular dementia correlates with a low consumption of dairy

products, although research also links the consumption of whole fat

dairy products with cognitive decline. Adherence to a Mediterranean

diet slows cognitive decline as the elderly progress from Mild

Cognitive Impairment to full-blown Alzheimer's. Hence findings

encourage eating more fish, non-starchy vegetables and fruits in a

diet low in foods with added sugar.

____________

Skim

milk:

The calcium and Vitamin D in skim milk can lower blood pressure

from three to ten percent (Bauer, 2014, p. 1).

Spinach:

The potassium, folate, and magnesium in spinach can help lower

blood pressure (Bauer, 2014, p. 2).

Sunflower

seeds:

Unsalted sunflower seeds are “a great source of potassium”

Bauer, 2014, p. 3).

Beans:

The soluble fiber, magnesium, and potassium found in black, white,

navy, lima, pinto, and kidney beans lowers blood pressure and

improves cardiovascular health (Bauer, 2014, p. 4).

Baked

white potatoes:

Potatoes contain both magnesium and potassium. When a body's

potassium levels are low, it contains too much salt (Bauer, 2014, p.

5).

Bananas:

Bananas are “packed with potassium” (Bauer, 2014, p. 6).

Soybeans:

Soybeans contain potassium and magnesium (Bauer, 2014, p. 7).

Dark

chocolate:

Eating just 30 calories or a single square of dark chocolate daily

lowers blood pressures without gaining weight after 18 weeks

(Bauer,2014, p. 8).

DASH

[Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension diet] towards

lower blood pressure:

Emphasize

fruit, vegetables, and low-fat dairy selections;

Cut

back on saturated fat, cholesterol rich, and trans foods;

Consume

more whole grains, fish, poultry, and nuts;

Limit

sodium, sweets, sugary drinks, and red meats.

Reduce

salt intake:*

Don't

automatically reach for the salt;

Read

labels when shopping;

Select

fewer processed and packaged foods;

Ask

restaurant chefs not to add salt to menu selections, or choose

lower sodium options on restaurant menus.

Realize

that drinking moderately to lower blood pressure depends on other

lifestyle factors.

Develop

a sensible weight-loss plan:

Set

weight loss goals after deciding whether to participate in a

structured program or to simply limit portion sizes;

Understand

weight loss personalities: Impulsive, oblivious, uptight,

tenacious, or sociable;

Double-up

on diet and exercise: Only a combination of diet and exercise

leads to weight loss.

Adopt

a safe exercise plan:

Moderate

aerobic exercise for at lest 30 minutes daily at least five days

per week confers blood pressure lowering benefits.

To

stick with an exercise regime, “make it fun” and if possible,

“exercise with a friend”.

*Decreasing

Salt Intake

|

| Most salt comes from processed foods. |

He,

F. J., Li, J., and MacGregor, G. A. (2013, April). Effect of

long-term modest salt reduction on blood pressure. The

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews,

4, CD004937. doi: 10.1002/146551858.CD004937.pub2. [Abstract only].

Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23633321

This

meta-analysis searched Medline, Embase, the Cochrane Hypertension

Group Specialized Register, the Cochrane Central Register of

Controlled Trials, and a reference list of relevant articles for

randomized trials that focused on a “modest” reduction of salt

intake and a duration of at least four weeks and found that a modest

reduction in salt intake for at least a month's reduction causes a

significant drop on blood pressure in hypertensive participants as

well as those with normal blood pressure irrespective of their gender

and ethnicity.

Rebholz,

C. M., Gu, D., & Chen, J., et

al.

(2012, October 1). Physical activity reduces salt sensitivity of

blood pressure: The Genetic Epidemiology Network of Salt Sensitivity

Study. American

Journal of Epidemiology,

Suppl. 7, S106-13. doi: 10 1093/aje/kws266. [Abstract only].

Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23035134

A

dietary study conducted between October 2003 and July 2005 that

included a seven-day low-sodium intervention followed by a seven-day

high sodium intervention adhered to by 1,906 rural northern Chinese

age 16 and over found that physical activity may be “particularly

effective” in lowering blood pressure” among those individuals

who are “salt sensitive”.

Try

seasoning potatoes with pepper, parsley, onion, green peppers,

chives, or pimento (Seasoning without salt, 2015, para. 2).

Yang,

Q., Liu,T.,and Kuklina, E.V., et

al.

(2011, July 11). Sodium and potassium intake and mortality among US

adults: Prospective data from the Third

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

Archives

of Internal Medicine,

171*13), 1183-91 doi: 10.1001/archintermed.2011.257. [Abstract

only]. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21747015

The

Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Linked

Mortality File (1998-2006), a prospective cohort study of a

nationally representative sample of 12,267 American adults

associated higher sodium intake with all causes of mortality.

Conversely, it also associated lower mortality risk with higher

potassium intake. Moreover, the individual's sex, ethnicity, BMI,

hypertension status, education and physical activity levels didn't

really differ. Accordingly, the findings suggest that a higher

sodium to potassium ratio correlates with an increased risk of

cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality while a higher sodium

intake corresponds with an increased mortality rate in the general

United States population.

Zhang,

Z., Cogswell, M. E., and Gillespie, C., et

al.

(2013, October 10). Association between usual sodium and potassium

intake and blood pressure and hypertension among U. S. adults: NHANES

2005-2010.

PloS One,

10, 8(10), e75209. doi: 10.1371/journal/pone.0075289. [Abstract

only]. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24130700

After

analyzing data on 10,563 study participants over age 20, who were

neither taking medication to control their blood pressure, nor were

on a low-salt diet, the National Health & Nutrition Examination

Survey found that the average intake of sodium, potassium, and

sodium-to-potassium ratios were 3,569 mhld, 2,745 mgld, and 1.41 mgld

respectively, so researchers thus concluded that the nigh sodium and

low potassium consumption levels correlated with hypertension.

A

Complete Physical Activity Program:

Include

aerobic and strength training activities in an exercise program, but

not necessarily in the same session, thus maintaining or improving

cardiovascular, respiratory and muscular fitness (Hagberg, 2011, p.

1, para. 1). The ACSM recommends 30 minutes of moderately intense

physical activity five days a week or 20 minutes of vigorous activity

three days a week to maintain cardiovascularhealth (Hagberg, 2011, p.

1, para. 2).

Aerobic

exercise includes walking, running, stair climbing, cycling, rowing,

cross-country skiing, and swimming (Hagberg, 2011, p. 1, para. 3).

Strength training should be performed at least twice weekly,

performing 8 to 12 reps of eight to ten different exercises that

target all muscle groups (Hagberg, 2011, p. 1, para. 4).

Treatment

Choices:

Once

under medications, individuals with hypertension can further

decrease their blood pressure through physical activity.

Mild

to moderate hypertension can also benefit from healthy lifestyle

changes, such as increasing physical activity, decreasing salt

intake improving diet, and losing weight.

Exercise

decreases systolic and diastolic blood pressure levels from five to

seven points as early as from three to four weeks after starting an

exercise program.

Physical

activity also helps control weight and improve blood pressure,

cholesterol, and glucose levels.

Individuals

diagnosed with ”pre-hypertension” (120 to 139 systolic pressure

and 80 to 89 diastolic pressure also need to exercise regularly.

(Hagberg,

2011, p. 1, para. 6)

How

Should You Exercise?

Beneficial

exercises include brisk walking, taking the stairs, moderate to

vigorous yard or house work, jogging, swimming, and cycling.

Moderate exercise may reduce blood pressure as much as strenuous

activity. The side affects of exercise, however, are “generally

positive” (Hagberg, 2011, p. 2, para.1-4).

Ways

to Improve Your Health:

Physical

activity can be added without making major lifestyle changes

(Hagberg, 2011, p. 2, para.5). Simple changes include parking

further away from destinations, taking the stairs, going for a walk

on the lunch hour, walking to a restaurant for lunch, taking children

to the park, mall walking in bad weather, waking up 30 minutes early

to exercise, and varying physical activities to make exercise

interesting (Hagberg, 2011, p. 2, para. 6).

Staying

Active Pays Off:

Moderate

physical activity significantly contributes to longevity, but

exercise can also help dieters stay on a diet and lose weight

(Harberg, 2011, p. 2, para. 7-8).

The

First Step:

Ask

some important questions that will access cardiovascular health

before increasing physical activity (Harberg, 2011, p. 2, para. 9).

Lifestyle

changes can lower blood pressure, possibly eliminating the need for

prescription drugs. Everyone, however, who suffers from high blood

pressure should look for natural ways to lower high blood pressure

(Harding, 2015, p. 1).

Exercise

more:

By exercising aerobically 30 minutes daily most days per week,

systolic blood pressure (the top number) can be lowered three to

five points, and diastolic blood pressure (the bottom number) can be

lowered two to three points. Pick an enjoyable activity and stick

with it (Harding, 2015, p. 2). Thus, everyone—whether one suffers

from hypertension or not—should take part in brisk aerobic

exercise for at least 30 minutes at a time five or six days per

week;

Eat

bananas

[or other foods high in potassium]: Select from choices like baked

potatoes with their skins, orange juice and non-fat yoga (Harding,

2015, p. 3);

Cut

salt:

Individuals already diagnosed with hypertension should limit their

salt intake to 1,500 milligrams daily, sticking with whole foods and

checking nutritional labels for sodium content (Harding, 2015, p.

4);

Don't

smoke:

Smokers average a higher risk for hypertension because lifestyle

factors often associated with smoking; for example, heavy alcohol

consumption and lack of exercise, increase blood pressure (Harding,

2015, p. 5);

Lose

weight:

Since extra weight makes the heart work harder, losing weight

lightens its cardiovascular work load (Harding, 2015, p. 6);

Cut

back on alcohol:

Drinking too much can elevate blood pressure. Accordingly, excess

drinking in both men and women increases the risk of hypertension

(Harding, 2015, p. 7);

De-stress:

Look for ways to manage stress (Harding, 2015, p. 8);

Yoga:

Yoga instruction teaches measured breathing that reduces

hypertension, which reduces hypertension since it modifies the

autonomic nervous system (Harding, 2015, p. 9);*

Skip

caffeine:

The caffeine in coffee, and to a lesser extent the caffeine in tea

and soda, causes short spikes in hypertension, so those diagnosed

with hypertension should limit their intake to two or less servings

of caffeine daily (Harding, 2015, p. 10); *

Meditate:

Daily meditation, whether it features chanting, breathing, or

visualization, lowers blood pressure (Harding, 2015, p. 11).*

*Yoga

& Meditation

|

| Yoga and meditation reduce stress, lowering blood pressure. |

Bai, Z.,

Chang, J. & Chen, C.,

et al.

(2015, February 12). Investigating the effect of transcendental

meditation on blood pressure: A systematic review and meta-analysis.

Journal

of Human

Hypertension.

doi: 1038/jhh.2015.6. [Abstract only]. Retrieved from

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25673114

After

searching Medline, Embase, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, and

Chinese bio-medical literature databases for articles on

Transcendental Meditation through 2014, researchers first used the

Cochrane Collaboration's quality assessment tool, researchers zeroed

in on 12 studies that compared with TM groups with control groups.

They then discovered that TM had a greater effect on systolic blood

pressure among older participants, those with a higher initial blood

pressure rate, and women. As for controlling diastolic blood

pressure, TM works only as a short-term interventions for those

individuals already diagnosed with higher blood pressure.

Chu,

P., Gotink, R. A., and Yeh, G. Y. , et

al.

(2014, December 15). The effectiveness of yoga in modifying risk

factors for cardiovascular disease and metabolic syndrome: A

systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.

European

Journal of Preventive Cardiology,

pii: 204787314562741. [Abstract only]. Retrieved from

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25510863

After

reviewing 1,401 electronic records written in English found via

Medline,

EMBase,

CINAHL, PsycINFO, and the Cochrane

Central Register of Controlled Trials,

researchers found that compared to non-exercise controls, yoga

significantly improved body mass index, systolic blood pressure,

low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and high-density lipoprotein

cholesterol. Significant changes also took place in body weight,

diastolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, triglycerides, and heart

rate. However, no significant differences existed between yoga and

exercise in their ability to bring down blood pressure.

Mashyal,

P., Bhargav, H., & Raghuran, N. (2014, October-December). Safety

and usefulness of Laghu shankha prakshalana in patients with

essential hypertension: A self-controlled clinical study.

Journal of Ayurveda and Integrative Medicine,

594), 227-35. doi:10.4108/9759475.131724. [Abstract only]. Retrieved

from

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25624697

This

Bengalurui, India, self-controlled study recruited 32 patients

diagnosed with mild to moderate hypertension to participate in a

residential yoga therapy program. Patients took part in a daily

routine that featured six hours of yoga therapy that included

physical poses, relaxation sessions, pranayana and meditation as well

as the drinking of warm water. Participants significantly reduced

their systolic and diastolic blood pressure and pulse rates

immediately following yoga sessions. Moreover, after a week of yoga

therapy they also significant saw a drop in their blood pressure.

Eight

weeks of mindfulness meditation performed by those diagnosed with

pre-hypertension, but who as of yet weren't taking any medication,

didn't have any affect. However, researchers theorized that

meditation therapy might help patients already taking blood pressure

medications take them more consistently (Raven, 2013, October 4,

para. 2 & 5).

The

101 participants in the study averaged a blood pressure of 135/82 mm

Hg, above normal, but not yet “high”. Half started

mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) immediately, but half were

wait listed to take the class later (Raven, 2013, October 4, para.

9-10). Mindfulness participants, aged 20 to 75, attended eight

weekly sessions as well as a day-long retreat and received

instructions to practice stress reduction therapy for 45 minutes

daily. Additionally, they received counseling that amounted to

standard-issue medical advice: Use less salt, quit smoking, and

exercise more (Raven, 2013, October 4, para. 11-12). A 2007 study

published by the US Agency for Healthcare Research Quality found that

Zen Buddhist meditation and Qi Gong “significantly reduced” blood

pressure (Raven, 2013, October 4, para. 17).

Telles,

S., Sharma, S. K., and Balkrishna, A. (2014, November 19). Blood

pressure and heart rate variability during yoga-based alternate

nostril breathing practice and breath awareness. Medical

Science

Monitor Basic Research, 20,

184-93. doi: 10.12659/MSMBR.892963.

[Abstract only]. Retrieved from

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25408140

Researchers

evaluated heart-rate variability, non-invasive arterial blood

pressure, and respiration rate during Alternate Nostril Yoga

Breathing (ANYB) and breath awareness sessions of 26 male volunteers

with the mean age of 23.8 years, assessing their performance five

minutes before the 25 minute yoga routines began, 15 minutes into the

exercise, and five minutes afterward, and they found that during

ANYB, the participants experienced a significant decrease in

systolic blood pressure as well as their respiration rate.

*Increasing

Potassium Intake

|

| Bananas aren't the only foods rich in potassium. |

Miller,

Brian. (2015). 15 foods that are high in potassium. User's

Manual: Your Heart Health.

Health.com.

Retrieved from

http://www.health.com/health/gallery/0,,20721159,00.html

Decreasing

salt in taking and adding potassium-rich foods to a diet may cut the

risk of stroke by 21 percent. Since potassium protects blood vessels

from oxidation damage and keeps the walls of blood vessels from

thickening. While taking too much potassium as a supplement can be

dangerous, a potassium enhanced heart-healthy diet can provide the

4,700 milligrams of potassium adults need each day (Miller, 2015. p.

1).

The

following foods are rich in potassium: sweet potatoes, tomato sauces,

beet greens, beans, yogurt, clams, prunes, carrot juice, molasses,

cod, halibut, tuna, and rainbow trout,soybeans, winter squash,

bananas, milk, and orange juice (Miller, 2015, p. 2-16).

Potassium

triggers the heart to squeeze blood through the body, additionally

enabling muscle movement and nerve function as well as helping the

kidneys to carry blood (Potassium and your heart, 2014, para. 1-2).

Fruits and vegetables are the best sources of potassium, although

potassium is also found in dairy products, whole grains,meat, and

fish (Potassium and your heart, 2014, para. 3). A diet rich in

potassium lowers systolic blood pressure by ten points while taking

potassium supplements only lowers SBP lowers it by just eight points.

Many diets that lower cholesterol levels also are high in potassium

(Potassium and your heart, 2014, para. 6-7). The US Department of

Agriculture recommends that healthy individuals consume 4,700

milligrams of potassium daily (Potassium and your heart, 2014, para.

9).

A

2010 advisory committee found a short fall in United States potassium

consumption while moderate evidence associated potassium intake with

lower blood pressure. Adequate potassium levels also mitigate

age-related bone loss and the reduces kidney stones. Americans thus

need to increase their potassium intake above current levels for

optional health, although the affect of increased fruit and vegetable

consumption for short periods of time has proved disappointing.

Simultaneously, western diets have led to a decrease in potassium

intake with the reduced consumption of fruits and vegetables.

Consuming white vegetables, like potatoes, however, correlates with a

decrease in the risk of stroke. Potatoes remain the highest source

of dietary potassium provided the diner limits salt intake.*

Moreover, a low-potassium to sodium ratio strongly correlates with

cardiovascular risk.

Potassium

helps to lower blood pressure by “balancing out the negative

effects of salt”. Salt conversely reduces the kidneys' ability to

remove excess fluid. It's best to get potassium from natural sources

and avoid supplements (Why potassium, 2008, p. 1). Five servings of

fruits and vegetables daily should provide enough potassium to lower

blood pressure while also cutting the risk of certain cancers, bowel

problems, heart attacks, and stroke. Potatoes, sweet potatoes,

bananas, tomato sauce without the added salt and sugar, orange juice,

tuna, yogurt, and fat-free milk all are sources of potassium (Why

potassium, 2008, p. 2).

___________

If

I have high blood pressure, what can I do take care of myself?

Those

diagnosed with high blood pressure [as well as prehypertension] can

control their blood pressure in eight ways:

Eat

a better diet, which may include reducing salt;

Enjoy

regular physical activity;

Maintain

a healthy weight;

Manage

stress;

Avoid

tobacco smoke;

Comply

with medication prescriptions;

If

you drink, limit alcohol;

Understand

hot tub safety.*

(Prevention

& treatment of HBP, 2014, August 4, para. 1)

Lifestyle

modifications are essential since by adopting a heart-healthy

lifestyle, those at risk can

reduce

high blood pressure

prevent

or delay its development;

enhance

the effectiveness of blood pressure medications;

lower

the risk of heart attack, heart disease, stroke, and kidney disease.

(Prevention

& treatment of HBP, 2014, August 4, para. 2-4)

Here's

how to do your part:

Be

informed;

Do

your part to reach your treatment goals;

Change

your life and reduce your risks;

Take

medication if it is prescribed for you [if blood pressure is 140/90

or higher].

(Prevention

& treatment of HBP, 2014, para. 5-9)

Once

a treatment program becomes routine, maintaining a lower blood

pressure is easier (Prevention & treatment of HBP, 2014, para.

10).

Managing

blood pressure is a lifetime commitment, so take a pledge to do so

(Prevention & treatment of HBP, 2014, para. 11).

*Practicing

Hot Tub Safety

|

| Those with high blood pressure should limit hot tub use. |

Individuals

with high blood pressure “should tolerate” saunas and hot tubs if

they aren't having a hypertensive crisis (Hot tub & sauna use,

2014, August 14, para. 1). Heat from these sources opens up blood

vessels in a process known as vasodilation that also happens after

taking part in brisk aerobic exercise (Hot tub & sauna use, 2014,

August 14, para. 2). Those diagnosed with high blood pressure

shouldn't move back and forth between cold water and a hot tub or

sauna since this could increase blood pressure. They also shouldn't

drink alcohol while using a sauna or hot tub (Hot tub & sauna

use, 2014, August 14, para. 3).

Sudden

or extended immersion in hot water can superheat the body and stress

the heart (Hot tubs, 2014, July 3, para. 1). Accordingly, if older

and middle-aged adults with potential cardiovascular problems receive

the go ahead to soak in a hot tub, they must regulate water

temperature, limit soaking time to no more than ten minutes, and stay

hydrated by drinking water (Hot tubs, 2014, July 3, para. 4).

When

the body super heats, blood vessels dilate to cool the body,

diverting blood away from the body core to the skin, so the heart

rate and pulse increase to counteract a drop in blood pressure (Hot

tubs, 2014, July 3, para.7). For those individuals with

cardiovascular disease, this could over tax the heart leading to a

loss of adequate blood pressure, a corresponding increase in blood

pressure, dizziness or faintness, nausea, abnormal heart rhythm,

inadequate blood flow to the heart or body, and heart attack (Hot

tubs, 2014, July 3, para. 5). Beta blockers and diuretics can further

contribute to the hot tub user's medical problems (Hot tubs, 2014,

July 3, para.6). Anyone using a Jacuzzi or hot tub should make sure

the water temperature isn't too high,should stay hydrated, and soak

for only brief periods of time (Hot tubs, 2014, July 3, para. 8).

Lose

extra pounds and watch your blood pressure:*

Men

are at risk if their waist measures more than 40 inches or 102

centimeters; Asian men are at risk if their waistline measures more

than 36 inches or 91 centimeters;

Women

are at risk if their waistline measure more than 35 inches or 91

centimeters—that's a Misses 16. Asian women are at risk if their

waistline measures more than 32 inches or 81 centimeters—that's a

Misses 10.

Exercise

regularly:

Eat

a healthy diet:

Reduce

sodium in your diet:

Europeans

and Asians under age 51 should limit sodium to 2,300 milligrams a

day or less; all African Americans and everyone over age 51 should

limit sodium intake to 1,500 milligrams daily.

Track

how much salt is in your diet: Record what you eat and drink.

Eat

fewer processed foods: Limit or eliminate potato chips, frozen

foods, bacon, and lunch meats.

Don't

add salt: Use herbs or spices instead.

Limit

the amount of alcohol you drink:

Avoid

tobacco products and second-hand smoke;

Cut

back on caffeine;

Reduce

your stress;

Monitor

your blood pressure at home and make regular doctor appointments:

Get

support from family and friends.

(10

Ways, 2012, July 19, p. 1-2)

*Weight

Management

|

| Waist size predicts hypertension. |

Obesity

management interventions delivered in primary care for patients with

hypertension or cardiovascular disease: A review of clinical

effectiveness. (2014, July). Canadian

Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health.

[Excerpt only]. Retrieved from

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25473691

Since

patients diagnosed with hypertension often fail to translate

behavioral changes associated with weight loss into long-term

behavioral maintenance, prescribing anti-obesity drugs might be a

good strategy for those patients that can safely tolerate this

strategy. Weight loss improves cardiovascular risk factors like

glycemic control and the reduction of cholesterol levels. Weight

loss, in turn, increases physical activity, reduces the risk of

atherosclerosis, cardiovascular events, stroke, and type 2 diabetes.

A reduction in triglycerides and an increase in HDL cholesterol

occurs with as little as a five to ten percent reduction in body

weight.

Tyson,

C.C., Appel, L. J., & Vollmer, W. M., et

al.

(2013, July). Impact of 5-year weight change on blood pressure:

Results from the Weight Loss Maintenance trial. Journal

of Clinical Hypertension.(Greenwich,

Conn.), 15(7), 458-64. doi: 10.1111.jch.12018. [Abstract only].

Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23815533

Researchers

evaluated participants in a longitudinal weight loss maintenance

regime for weight loss, weight stability, and weight gain at a year,

30 months, and five years, respectively, observing correlations

between weight change and diastolic and systolic blood pressure.

Mean systolic blood pressure increased in participants who either

gained weight or maintained a stable weight, but they didn't increase

in the weigh loss group while diastolic blood pressures remained

stable for five years. These results thus suggest that continued

gradual, modest weight loss may sufficiently lower blood pressure in

the long term.

How

Abdominal Fat Increases Disease Risk

More

than sixty years ago a French physician associated larger waists

with a higher risk of premature cardiovascular disease (Vague, J.,

1947, La

diffrentiation sexuelle.

Facteur

determinant des formes de

l'obesity.

Press

Med.,

30, 339-40).

Since

then, follow-up studies have verified his finding while linking

abdominal-obesity with the risk of developing type 2 diabetes even

after controlling for Body Mass Index (BMI) (Waist size, 2015, para.

1).

Apple-

and Pear-shaped Body Types

Abdominal

obesity results in an apple-shaped body type. However, two popular

ways to determine abdominal obesity are measuring the waist's

circumference and determining waist size compared to hip-size, or the

waist-to-hip ratio (Waist size, 2015, para. 2-3).

Even

in those individuals who aren't otherwise overweight but who have a

large waist are at a higher risk for health problems than those with

a narrower waist. The Nurses' Health Study (2008),

which

looked at the relationship between waist size and deaths from heart

disease and cancer in middle-aged women, for example, found that

after 16 years women who had the largest waist sizes (35 inches or

higher) doubled their risk of heart disease when compared with those

women who had the smallest waist size (less than 28 inches).

Moreover risks increased with every added inch to the waist (Waist

size, 2015, para. 4-5). Even women was a normal BMI were at risk if

they carried more of their body weight around the waist (Waist size,

2015, para. 6). The Shanghai Women's Health Study (2007) came up

with the same findings (Waist size, 2015, para. 6).

Larger

waists are so risky because the fat surrounding the liver and other

abdominal organs is metabolically active, thus releasing fatty acids,

inflammation, and hormones that lead to higher LDL cholesterol,

triglycerides, blood glucose levels, and a rise in blood pressure

(Waist size, 2015, para. 7).

Which

Is Best: Waist or Waist-to-Hip?

A

2007 study associated both waist-to-hip and weight circumference with

cardiovascular risk while additional studies have found they predict

future type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and cancer diagnoses (Waist

size, 2015, para. 8-9).

__________

Go

for power walks:

Walk briskly for at least 30 minutes daily;

Breathe

deeply:

Practice qigong, yoga, or tai chi;

Pick

potatoes:

Regularly include potassium-rich foods, like potatoes, in a

heart-healthy diet;*

Be

salt smart:

Cut sodium by stirring away from processed foods;

Indulge

in dark chocolate

[in moderation];.

Take

a supplement:

Ask the family doctor about taking coenzymeQ10;

Drink

a little alcohol:

Moderate drinking lowers blood pressure;

Switch

to decaf coffee;

Take

up

[hibiscus] tea;

Work

a little less

[more than 41 hours per week];

Relax

to music:

Listen to soothing, classic, Celtic, or Indian music for 30 minutes

daily];*

Seek

help for snoring;

Jump

for soy

[as well as nuts].

Obviously,

all cooked foods need to be broiled, grilled, or boiled rather than

fried.

*Taking

up Hibiscus Tea:

|

| Drinking hibiscus or tisane tea lowers blood pressure. |

Some

researchers think hibiscus might be an effective treatment for high

blood pressure. WebMD

reviews rate it “possibly effective” along with such common

alternative treatments for high blood pressure and hypertension as

co-enzyme Q-10, fish oil, and potassium while not enough evidence

exists to truly evaluate whether soy is an effective treatment for

high blood pressure.

Hopkins,

A. L., Lamm, M. G., and Funk, J. L. et

al.

(2013, March). Hibiscus sabdarrffa

L. in the treatment of hypertension & hyperlipidemia: A

comprehensive review of animal and human studies. Fitoterapia,

85 (84-94). doi: 10.2026/j.fitnote.2013.01.003. [Abstract only].

Retrieved from

Hibiscus

sabdarrffa is a home remedy for treating hypertension and

hyperlipidenia without adverse side effects unless less taken in

high doses, although it does act as a diuretic. Animal studies show

that Hibiscus sabdarrffa extract reduces blood pressure in a dose

dependent manner, and randomized clinical trails show that hibiscus

tea significantly lowers systolic and diastolic blood pressure in

adults with prehypertenson as well as moderate hypertension and type

2 diabetes, making it at least as effective at lowering blood

pressure at Captropril, but less efficient than

Lisinopril.

McKay,

D. L., Chen, C.Y., and Saltzman, E., et

al.

(2010 February). Hibiscus sabdariffa L. tea (tisane) lowers blood

pressure in pre-hypertensive and mildly hypertensive adults. The

Journal of Nutrition,

140(2), 298-303. [Abstract only]. Retrieved from

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20018807

A

randomized, double-blind placebo controlled six week trial of 65 pre-

and mild hypertensive adults age 30 to 70 not taking blood pressure

lowing medications found that daily drinking three 240 milliliter

servings of hibiscus

tea lowered systolic blood pressure when compared with a placebo. Tea

sippers with a high systolic blood pressure at baseline exhibited a

greater response to hibiscus tea.

*Relaxing

to Music:

|

| Classical Indian music lowers blood pressure. |

Brookes,

Linda. (2005). Significantly new definitions, publications, risks,

benefits: Music can reduce blood pressure, depending on the tempo.

Medscape

Multispecialty.

Retrieved from http://www.medscape.org/viewarticle/514644_6

Listening

to music with a fast tempo increases blood pressure while listening

to slower music lowers it. Introducing a pause, in turn, lowers

blood pressure even further, and these effects particularly apply to

individuals who have had musical training, according to a study

published in the British medical journal, Heart (Brookes, 2005, para.

1). Study participants in Italy and the United Kingdom listened to

six selections played in random order whereupon researchers

documented that faster tempos and simpler rhythmic structures

increased ventilation, breathing rate, systolic and diastolic blood

pressure, mid-cerebral artery flow velocity and heart rate while

slow music exercised less effect, although Indian raga induced a

“significant drop” in heart rate (Brookes, 2005, para. 2-4).

*Jumping

for Soy:

|

| Soy can lower blood pressure, but it does have its own hazards. |

Mohammadifard,

N. , Salehi-Abarghovei, A., and Salas-Salvado, J. (2015, March). The

effect of tree nut, peanut, and soy nut consumption on blood

pressure: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized

controlled clinical trials. The

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition.

pii. Ajcn091595. [Abstract only]. Retrieved from

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25809855

Scanning

Medline, SCORPUS, ISI Web of Science, and Google Scholar between 1958

and October 2013, researchers found that nut consumption leads to a

“significant reduction” in systolic blood pressure in study

participants without type-2 diabetes. Pistachios most effectively

reduced systolic and diastolic blood pressure.

Stradling,

C., Hamid, M., & Fisher, K., et

al.

(2013, December). A review of dietary influence on cardiovascular

health: Part 1. The role of dietary nutrients. Cardiovascular

& Hermatalogical

Disorders

Drug Targets,

13(3), 208-30. [Abstract only]. Retrieved from

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24304234

Upon

searching the Cochrane Library database between 2006 and 2012,

researchers found evidence that “underpins current dietary

cardiovascular guidelines—replacing saturated and unsaturated fat,

consuming whole grains or carbohydrates of low on the glycaemic

index, increasing the consumption of fruit, cruciferous vegetables,

nuts, and oily fish. Additionally, adding soya protein to one's diet

and reducing sodium intake reduces cardiovascular disease risk.

Furthermore, dietary changes, such as consuming fewer animal and

processed foods, results in a reduction in saturated fats.

____________

Selected Research Studies on the Affect

of Diet upon Blood Pressure

Research

also suggests that a diet that emphasizes fruits and vegetables as

well as including at least two servings of oily fish per week in the

diet help to lower blood pressure and improve cardiovascular health

and ward off Alzheimer's at the same time.

Afolayan,

A. J. & Wintola, O. A. (2014, April 3). Dietary supplements in

the management of hypertension and diabetes—a review. African

Journal of traditional, complementary, and alternative medicines:

AIRCAM/African Networks on Ethnomedicines,

11(3), 248-58. Retrieved from

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25371590

Orthodox

drugs used in the treatment of hypertension and diabetes may produce

adverse side affects like headaches, nausea, vomiting, stomach pain,

constipation, diarrhea, weakness, fatigue, and erectile dysfunction.

However, relying on vitamins, minerals, amino acids, herbs and other

botanical treatments as well as a diet that emphasizes fruits and

vegetables in many instances provide safer and less expensive

alternatives to conventional pharmaceuticals particularly in

third-world countries.

Mori,

T. A. (2014, September). Omega-3 fatty acids and cardiovascular

disease: Epidemiology and effects on cardiometabolic risk factors.

Food

& Function,

5(9) 2004-19. doi: 1039/c4fo009d. [Abstract only]. Retrieved from

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25062404

Clinical

and epidemiological studies support evidence that polyunsaturated

omega-3 fatty acid from fish and recommended dosages of fish oil

protects the cardiovascular system, favorably influencing risk

factors for blood pressure, vascular reactivity, and cardiac function

without being associated with any adverse effects, including the risk

of heavy bleeding. Health professions thus recommend two serving of

fish weekly. The general population should incorporate these

servings of fish in a diet plan that increases the consumption of

fruits and vegetables while moderating salt intake.

Rees,

K. Hartley, L., and Floers, N. et

al.

(2013, August). 'Mediterranean' dietary pattern for the prevention

of cardiovascular disease. The

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews,

12(80. CD009825. doi: 1002/14651858.CD009825.pub2. [Abstract only].

Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23939686

After

the Seven Countries Study found in the 1960s that countries

surrounding the Mediterranean experienced lower cardiovascular

disease mortality rates than Northern Europe and North America,

observational studies confirmed these findings, but clinical evidence

documenting the diet's benefits for the most part was lacking until

researchers searched electronic databases from 1946 to 2012. A

Mediterranean diet by definition has a high monounsaturated to

saturated fat ratio and features low to moderate red wine intake as

well as a high consumption of legumes, grains, cereals, fruits, and

vegetables while severely limiting meat and meat products while

increasing the amount of fish eaten, and only consuming dairy

products in moderation. Researchers eventually included 11 trials

and 15 papers in their survey, and this limited evidence suggests

that following a Mediterranean diet may benefit cardiovascular

health.

Wanjek,

Christopher. (2015, March). 'MIND ' your diet and protect against

Alzheimer's. Yahoo.com. Retrieved from

http://news.yahoo.com/mind-diet-protect-against-alzheimers-144212880.html

Following

the MIND diet as documented in the Online March issue of Alzheimer's

and Dementia, results in a 35 percent reduction in the risk of

Alzheimer's (Wanjek, 2015, March 25, para. 2, 4, & 11). The MIND

diet, which combines the DASH and Mediterranean diets, emphasizes

green leafy vegetables, along with other vegetables, nuts, berries,

beans, whole grains, fish poultry, olive oil, and wine. Conversely,

MIND dieters should avoid red meat, butter and stick margarine,

cheese, pastries, and sweets (Wanjek, 2015, March 25, para. 10).

___________

Addendum

August

31, 2015

The American Heart Association recommends that healthy

adults eat two servings of Omega-3 fatty fish weekly, although the University

of Maryland Medical Center cautions that three servings of Omega-3 fish week

may raise the rise of hemorrhagic stroke.

The Website also cautions that it’s important to consult a physician

before taking more than three grams of Omega-3 fatty fish capsules daily (Omega

3 fatty acid, 2015, para. 8 & 21).

Omega 3 fatty acids. (2015). University of Maryland Medical Center. Retrieved from http://umm.edu/health/medical/altmed/supplement/omega3-fatty-acids

___________

The links furnished on this Web page represent the opinions of their authors, so they complement—not substitute—for a physician’s advice.